As work began on Beauty and the Beast (1991), Disney animators were finally – finally – feeling confident again. Who Framed Roger Rabbit and The Little Mermaid had been critical and box office successes, and even The Rescuers Down Under, if not exactly a major hit, had at least allowed animators to work out computer animation techniques that they were eager to try on a new film. The animators were ready to return to the glory days of Disney animation, with a film that could be both a work of art and a box office success.

They succeeded beyond their wildest hopes.

Let’s get a few negative points out of the way. The film’s timeline does not make a lot of sense – it either takes place over an entire winter, or over a three day period. If the first, several internal elements make very little sense. For instance, how did poor LeFou survive standing outside Belle’s cottage, covered in snow, for several days? If the second, uh, how exactly did the countryside go from fall (the orange/red/yellow leaves at the beginning of the film) through winter (all that snow in the middle) through spring (the final scenes) in three days? I can only answer, fairy tale, and hope that’s enough.

(It was not enough for at least one exasperated six-year-old viewer.)

More seriously, yes, the climax of the film involves two men fighting over a woman. Yes, it has three characters called, sigh, the Bimbettes, or, in the stage version, the Silly Girls. Yes, one of the most famous sections involves a group of servants happily singing about how great it is to be back working for the aristocratic class again – this after they’ve spent most of the film enchanted thanks to the terrible temper of their aristocratic boss. And, of course, the film’s central message that “Beauty is found within” is sort of undercut when its one hideously ugly character is transformed into a outwardly handsome prince. And yes, this is a movie about a woman who falls for the guy that takes her prisoner. And yes, he really is a Beast and a jerk about it, yelling at her just because she, quite understandably, doesn’t want to have dinner with him under the circumstances, and… yeah, let’s hope this movie doesn’t take place over a three day period, because otherwise I’m kinda horrified.

I still love it.

A few possibly mitigating factors: for one, the Beast is a prisoner himself. While we’re on that topic, can we ask a few questions about what, exactly, was going on here? First, the not so small problem that the prince was answering his own doorbell – something not exactly standard at the time, and that’s before we learn that he has a small army of servants at that castle. Why didn’t one of the servants answer the door? Second, and more seriously, the decision by the enchantress to turn all of the human servants into living furniture, like, ok, so they didn’t do a great job of raising the prince up to be a nice guy, and yes, they clearly aren’t great at answering the door promptly, but this does seem to be a bit harsh. Especially since, as Disney executive Jeffrey Katzenberg revealed in later interviews, the prince was about ten at the time. Which is to say, fairy, you’re enchanting an entire castle just because a ten year old kid was rude to you? Have you considered some therapy for your slight—slight—overreaction to life? And third – given that this castle in some of the final scenes seems to be just a few hours march from the village, exactly how did all of this happen with apparently no one in the village aware that (a) a castle is there, and (b) it’s now enchanted? Or is that just part of the enchantment?

I suppose we could argue that the enchantress meant this only to be a learning experience, intending all along to set up a situation that would force Belle to the castle, where a chastened Beast would fall for her and vice versa, but if that was her plan—well, the Beast we originally meet isn’t chastened in the slightest. He’s angry. And although I don’t think he should be taking this anger out on Belle or her father, I do think that he has quite a few reasons to be angry—and to distrust anyone who happens to come knocking on his door.

After all, the last person who knocked on his door ended up both transforming him and linking his fate to a fragile, enchanted rose, for all intents and purposes imprisoning him in his own palace. The script makes that point explicit: his only connection to the world outside his castle is an enchanted mirror. The people who arrive after Belle are explicitly trying to kill him: they even sing about it. “KILL THE BEAST! KILL THE BEAST!” Under the circumstances I probably wouldn’t be too thrilled to see visitors either.

It’s also not surprising that all of this causes his temper to deteriorate still further. So quite apart from the “Who could ever learn to love a Beast?” question, we have a “Who could ever learn to love a Beast imprisoned in his own castle? A Beast so angry that he has ripped the once elegant furnishings of his room apart?” Indeed, if you ask me, the real villain of the film isn’t Gaston, who when not persecuting harmless crackpots and girls who want nothing to do with him and decorating his home with antlers, does round up the villagers to fight a dangerous beast, but rather the enchantress who PUT THE DANGEROUS BEAST NEAR THE VILLAGE IN THE FIRST PLACE.

Another mitigating factor: yes, the Beast takes Belle prisoner – but doesn’t lock her away. She is able to flee, and she returns on her own volition. Yes, this is partly because the Beast followed her and saved her life, and she feels a sense of gratitude – but even still; she had the opportunity to return to the village, and didn’t take it. Maybe she wanted to see all of those plates dancing again. And, of course, after their dance, he lets her go. Without, I might add, the conditions that bound Beauty in the literary versions, who must return within a certain time frame. The Beast simply lets her go, and then falls into a profound depression. Not once does he consider going after her, even though – since by this time the rose is nearly gone – it means his almost certain entrapment in a form that he hates.

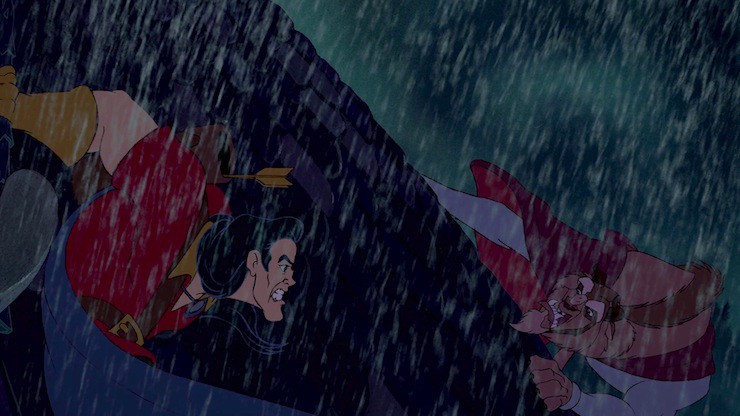

And a third mitigating factor: only one of the two men is really fighting about or over Belle in that last scene. The Beast is largely fighting in self-defense, and it takes a moment before he’s even willing to do that. His first reaction to the arrival of the villagers is to say “it doesn’t matter now,” which, GRATEFUL THANKS FROM ALL OF YOUR SERVANTS CURRENTLY UNDER ATTACK, BEAST, and if you’re going to be such a downer about that, how about AT LEAST coming down to the hall to give yourself up so your servants aren’t at (as much) risk, although it’s possible that that the freaked out villagers would have attacked the dancing furniture anyway, if only out of a hatred for Broadway musicals. I don’t know. In any case, Beast only really starts to fight back when he sees that Belle has returned, and all he demands is that Gaston leave his castle. Gaston is the one fighting over Belle, and Gaston has already been established as a villain.

And the way the whole transformation sequence kinda undercuts the “Beauty is found within” moral message? I’d argue it’s undercut well before that, because the guy running around terrorizing mostly harmless inventors who stumbled into his castle? Yeah. Not exactly gleaming with inner beauty no matter how understandable that anger is, changing the message of “Beauty is found within,” to “Beauty is found once you change your behavior patterns.”

The servants? Um. Hmm. Um. Oh, I know – that particular number allows them to do a little more dancing and singing and a little less manual labor, right, so that explains it?

Maybe?

No?

Ok, so that one’s a bit difficult to explain away.

But the real mitigating factors are, of course, pretty much everything else in the film: the animation – Disney’s most beautiful work since Sleeping Beauty – the score, the songs, the tight, efficient script, and, can it be? Sacre bleu! Actual character development, for the first time in any Disney film since, well, Pinocchio? Granted, it’s just one character, but let’s take what we can get here.

What’s surprising about this is that all of this happened in a film developed and animated in a rush – Beauty and the Beast was scripted, storyboarded, and animated in less than two years, half the four year time period used for most Disney animated films.

Most of that schedule was thanks to Jeffrey Katzenberg who, after watching the initial storyboards, threw the entire concept out, but refused to change the release date. Hearing this, the initial director understandably bowed out. Disney replaced him with Kirk Wise, who had joined Disney as an animator for The Great Mouse Detective, and Gary Trousdale, one of the very few people who started to work with Disney on The Black Cauldron and yet managed to have a relatively productive career with Disney afterwards. (Trousdale would eventually follow Katzenberg over to Dreamworks.)

The real direction and heart of the film, however, ended up coming from lyricist Howard Ashman, brought on with composer Alan Menken at Katzenberg’s insistence after their success with The Little Mermaid. Katzenberg wanted, not another non-musical adventure like The Rescuers Down Under, but another Broadway-style musical. Then dying of AIDS, Ashman poured his heart and soul into multiple aspects of the film: lyrics, story, characters, to the point where he neglected work on another film that he’d been hired to do (Aladdin.) Tragically, Ashman was to die eight months before the film was completed, although he was able to see bits of completed footage before he died.

He was also able to hear recordings of his songs, which featured some of his best lyrical work, even if I still must confess a slight personal preference for “Poor Unfortunate Souls” over “Gaston.” “Belle,” for instance, serves not just as a grand, Broadway-style introduction to the film, Belle and Gaston, but also contains bits like “But behind that fair facade/I’m afraid she’s rather odd,” the first of many delightful rhymes. “Something There,” and “Mob Song,” work not just as songs, but also to advance the story. Indeed, “Something There,” is really not much of a song on its own, but within the film, it works to swiftly show us that these two characters are starting to see each other in a very different light – that something might be there.

The showstoppers, though, were the soon to become a Disney signature song, “Be Our Guest,” and the title song, “Beauty and the Beast,” which, according to legend, was recorded by Angela Lansbury in just one take. (Legend fails to say just how many stabs Celine Dion and Peabo Bryson did for the version that played over the end credits, the version released as a single.) Both also featured the use of Disney’s CAPS system, developed for The Rescuers Down Under, and here used to create a chorus line of dancing tableware and the illusion of a sweeping camera on a dolly for the ballroom scene with Belle and the Beast.

Disney later incorporated “Be Our Guest” into several different commercials for its various theme parks and cruise ships, eventually making it Disney’s second most used song, outdone only by “When You Wish Upon a Star.” As a ballad about a grumpy monster and a girl who loves to read, “Beauty and the Beast” was not quite as useful for luring tourists, but the Dion/Bryson cover was a commercial success, and added to the profits for the film.

The decision to create a Broadway style musical also influenced the casting. Disney did snag a few well known non-singing voices, including Robby Benson, then known largely as 70s teenage heartthrob, for the Beast, and David Ogden Stiers, then best known for his role as pompous Major Charles Emerson Winchester III on M.A.S.H., as pompous Cogsworth, the start of a long career as a Disney voice actor. Otherwise, the filmmakers focused on Broadway and musical theatre actors. To get a rich, vibrating, near operatic tone for Gaston even in mere conversation, for instance, they hired opera and Broadway singer Richard White.

For Mrs. Potts, the producers snagged Angela Lansbury, then as now renowned not just for Murder, She Wrote, but also for her theatre and vocal work, and persuaded her to sing the film’s major ballad. Lansbury later called the role a gift to her three grandchildren. It also turned out to be a gift for Disney; the song – Lansbury’s version, not the tepid cover that plays over the credits – won an Academy Award, a Golden Globe Award and a Grammy. Jerry Orbach, another Broadway veteran, was brought in for Lumiere shortly before Law and Order took over the next 12 years of his life. For Belle, they hired Broadway singer Paige O’Hara, who infused a throbbing, emotional note into nearly every word.

That took care of vocal problems. The directors still, however, had to deal with the difficulties of attempting to animate the entire film in a shortened period – in two different locations on two different coastlines.

Pre-internet.

That particular problem was not the idea of anyone involved in the film, but rather of Disney executives, who wanted at least some of Beauty and the Beast animated at the smaller studio set up to allow tourists to watch animators at work, in what was then the Disney-MGM Studios theme park (now the Hollywood Studios theme park) in Florida. This proved particularly tricky during one of the most emotional scenes of the film, when Belle enters the West Wing and ends up having a fierce confrontation with the Beast. It was so emotional that the director ordered the voice actors to record their parts together, in contrast to most of the rest of the film, where Belle and Beast were recorded independently. When it came time to animate the scene, however, Glen Keane, drawing Beast in California, had to coordinate his work with Make Henn, drawing Belle for this particular scene in Florida. Keane would draw Beast, and then sort of scribble in a Belle, before sending off his drawings by overnight courier, and vice versa.

This is also why, if you pay attention, Belle does not always look precisely the same in all shots – she’s the work of different animators in different locations, and all of the overnight delivery systems in the world couldn’t compensate for those factors.

During all of this, both Howard Ashman and Jeffrey Katzenberg kept “suggesting” – read, ordering – changes to the story and script, forcing animators to tear up hours of drawings and start all over again. Katzenberg loved Chip, for instance, and demanded that the little teacup get a bigger role, but disliked the initial drawings for Gaston, the villain who uses antlers in all of his decorating, and who was, at least according to Katzenberg, not good-looking enough to drive home the point of looks versus character. Andreas Deja, who had started out at Disney in the uncomfortable position of working with Tim Burton’s very different artistic drawing style, now found himself in the only slightly more comfortable position of having to toss out his initial drawings and rework his initial concept – while under a tight deadline. Fortunately, as he admitted in later interviews, he had the examples of Hollywood actors with Gaston-like personalities to inspire him, making the “No one persecutes harmless crackpots like Gaston!” line completely credible.

And, after decades of use, Disney’s multiplane camera, developed for Snow White, was mostly non-functional, suitable only for museum displays. (It’s appeared in various museum tours and at the Hollywood Studios theme park.) Here, once again, the CAPS system designed for The Rescuers Down Under saved the film, allowing animators to create the same multiplane effect for the now nearly ubiquitous camera-moving-through-the-trees shot that had opened so many of its films from Snow White onwards, but also using CAPS to simulate the movement of an aerial camera.

The other advantage of CAPS, of course – and the main reason Disney encouraged its use – was cheapness; the money saved there allowed Beauty and the Beast to feature several scenes with multiple animated figures. Three scenes feature more than thirty individually animated figures, something not seen from the studio in decades, though The Little Mermaid had come close. In some cases, this was computer trickery, as in “Be Our Guest,” which simply had the computer copy hundreds of images of candles, tankards, cutlery and whirling napkins. In other cases – the fight between the villagers and the castle furniture; the shot of Belle walking through dozens of squabbling villagers, and the chase scene with the wolves, these were individually animated figures.

This had the side benefit of allowing animators to throw in a few background jokes here and there (watch the woman trying to fill her water jugs while Belle sings to the sheep about fairy tales), which along with comedic side characters like Cogsworth and LeFou, kept the film from getting too serious.

Which was fortunate, since at its center, Beauty and the Beast is a serious film, focused on two characters longing to escape. Like Ariel, Belle feels trapped in a world where she doesn’t feel she belongs. Unlike Ariel, Belle’s entrapment is more self-imposed, stemming from her love of her father and need to take care of him: there’s really nothing else (except, perhaps, a lack of money) keeping her in this provincial life, and although her father understandably tries to prevent her from becoming a prisoner of the Beast, he’s otherwise fully supportive of her. But Belle isn’t just looking for a different life: she’s looking for understanding. She’s looking for magic. She’s looking for a fairy tale – and falls in love with the Beast in part because, well, he is enchanted, and is in a fairy tale. At the same time, and to her credit, she’s quick to reject the fairy tale when her father needs her help – and equally quick to try to save the Beast when the villagers go after him.

And as much as the film might want to tell us – or more precisely, sing to us – that Belle falls for Beast after seeing “There’s something sweet/and almost kind” in the Beast, it seems more that these are two people who have fallen for each other in part out of mutual loneliness, in part because each recognizes that the other one wants something more than their current lives. Will a bookworm and a guy who apparently kept his huge library locked up behind heavy curtains be able to make it work? I don’t know, but if Belle decided to marry Beast for his library, I’m with her, and, after all, this is a fairy tale.

One quick note: some DVD editions of Beauty and the Beast include a five minute musical sequence, “Human Again,” added to the film. Written during early drafts of the film, and later replaced by “Something There,” “Human Again,” is not a terrible song, but the animation, done later, is not up to the original work, and interrupts the momentum of the film, not to mention the music, which is meant to go directly from “Something There” to the scene of Beast preparing for dinner – a scene that repeats the same melody. I couldn’t help thinking, with irritation, that the original team had removed this sequence for reason (they couldn’t fit it into the story) and should have focused on that reason.

The musical sequence also contains a small scene that irritates me more than it should: Belle, reading to Beast, asks him to read to her, and he confesses he can’t read, and she offers to teach him – starting with Romeo and Juliet. A, not exactly great beginner’s reading material there, Belle, and B, I don’t buy this: the Beast, at one point, was a prince, and if he has forgotten much of what he was taught (manners, using a knife and fork), much of that forgetting came from his transformation. Sure, the library was closed up until Belle arrived, but the same could be said for most of the castle.

Which is to say, if you can, try to watch the original edition.

For Disney, at least, Beauty and the Beast had a very happy ending. The film was a box office and critical success, and became the first animated feature to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture. (It lost to Silence of the Lambs, suggesting, not for the first time, that Academy voters were more interested in people eating each other than in people singing to each other.) It spawned two terrible direct to video sequels, Beauty and the Beast: The Enchanted Christmas and Beauty and the Beast: Belle’s Magical World, which at least made money, if not a positive artistic impression. The Christmas one is particularly terrible; if you haven’t seen it, continue to spare yourself. More positively, the film inspired a Broadway show and various attractions in nearly every Disney theme park, including stores, musical shows and, most recently, the Be Our Guest restaurant at Magic Kingdom. As one of the Disney Princesses, Belle makes regular appearances at the parks and Disney events, and has her own line of merchandise, including clothing, jewelry and housewares.

But above all, for Disney, Beauty and the Beast was a sign that The Little Mermaid had not just been a one-off fluke, a sign that its animators could produce popular, well reviewed entertainment that could even be viewed – by some critics – as high art. It was a sign that just maybe the studio could do more.

Disney CEO Michael Eisner saw the same signs, and was impressed enough by the profits from Beauty and the Beast that he ordered Jeffrey Katzenberg to keep the animation studio on its one film per year schedule, and approved plans for more ambitious animated films – films that could, for instance, look at U.S. history, or adapt major classics of French literature. The animators, excited, agreed to try.

But before the animators could really delve into those projects, they had one or two things to catch up with first. A small thing about a little lion cub – not much, really – and of course, this thing about a genie that Robin Williams had agreed to come on board for. Nothing close to Beauty and the Beast, of course, especially since Howard Ashman hadn’t been able to finish writing all of the lyrics for it, but still, it could be fun…

Aladdin, coming up next.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

I love this film. I wish my 3 year old daughter would hurry up and grow up a bit more so we can watch it together. I agree wholeheartedly about “Human Again” and wish my copy didn’t have it. Ditto “The Morning Report” in Lion King.

“Don’t whine, glasses!” –and I almost spilled my own from laughing. But it’s been some years since I checked this one out, and I remember something not so pleasant–it might have been in a spinoff movie–one of the enlivened inanimates was an organ, and it was one of the bad guys, and apart from I didn’t like to see my favorite instrument in the villain role, the deep cackling laugh of the guy doing its speaking voice triggered me right back to my stepfather molesting me… So I don’t plan to rewatch it. But I appreciate your critiques.

@Angiportus

You’re thinking of one of the direct to video sequels. There’s no organ in the original.

Re the timeline (Lefou in the snow, etc): the creative team knew it was a bit muddled, too–and that’s actually why “Human Again” was cut. It had this long middle section where the servants kept singing “Tick tock, the time goes…” and the writers didn’t want to draw too much attention to that, so they cut the song. A few years later, when they adapted the film into a Broadway show, they figured out that they could just get rid of the problematic middle section, and make the song about the servants’ excitement. So when they rereleased the film in 2002, they basically animated the scene from the show (just as the “Lion King” rerelease included an animated version of the (now cut) song, “The Morning Report). They tried to make it as seamless as possible, but yes, one can sort of tell it wasn’t there originally.

@1: If you don’t like the version that includes “Human Again,” you probably have the option of watching the original theatrical release. At least that’s the case with the DVD I have (dating back to 2003).

However, the organ in the terrible sequel was voiced by Tim Curry, which should count for something.

There are two reasons I personally love this movie: first, Belle and the Beast/Price fall in love over some actual period of time; second, Belle has more agency in this than so many of the Disney films I could list.

If anyone is planning to take a trip to Disney World, you really should make a reservation for the Be Our Guest restaurant. The food is pretty good, the interior is fantastic, and it’s the only place to get liquor in the Magic Kingdom

On the fraught topic of the film’s, er, problematic timeline and equally problematic characterization of the Enchantress, I think that a very convincing (and heartbreaking) biographical explanation can be pieced together from quotes, drawings and implications in the documentary Waking Sleeping Beauty and from Menken’s liner notes to the box set “The Music Behind the Magic”.

1) We know from Waking Sleeping Beauty that Howard Ashman was adamant on showing explicitly that the Beast was a child at the time of the curse. The directors tried to picture it and found it unintentionally hilarious (they compared their mental image to Eddie Munster), but when they raised this, Ashman went into a terrifying, volcanic rage that he seems not to have explained. They drew a vivid caricature of the scene which is shown in the film.

2) Menken makes it fairly clear at various places in the liner notes that some elements of the plight of the Beast are allegories for Ashman’s struggles with AIDS. If so, that completely explains the gigantic explosion at that meeting, and likewise why Ashman, who didn’t know Trousdale and Wise very well when it happened, didn’t want to explain why he felt so strongly about the issue.

So I’d say that the answer to timeline problem #1 (“How old is the Beast when the script implies that he is 10 or 11 at the time the curse was cast but the windows and the painting portray him as a young man?”) and to the motivations of the Enchantress problem are both: there’s evidence that, on a short production schedule and with intense personal feelings in play on both sides, production as a whole included some elements of both interpretations and hoped audiences, like the young Mari, wouldn’t notice. FWIW, I would argue that Glen Keane’s characterization of the Beast is much closer to Ashman’s traumatized victim of a bizarre injustice sort of causally related to one decision he made (a not inconceivable personal AIDS metaphor) than Trousdale and Wise’s subject of a quasi-divine judgement/behavior modification experiment. Which is yet another gigantic mitigating factor on top of the ones mentioned. I agree that this could be a terrifyingly sexist story depending on how it’s told. But not in this telling.

Likewise, “Human Again” is, I think, the key to the “Does this story take place over days or months?” timeline problem. The song’s original function (again, you have to hear the demo recording to know this, and it’s a little obscure) is very firmly on the side of “months”. Hence all the seasonal changes–the background artists got that message for most of the time they were working. The substitution of “Something There” was quite last-minute by animated film standards. So you solve the problem that the main characters haven’t said anything about their own feelings (and in general, the way that this story has to push the Broadway tradition of the “conditional love song” to its absolute limits, given that any declaration of love by the main characters literally ends the story). But you create the gigantic problem of making it look like an intelligent and sensitive woman changes that much in three days. (The demo, like the Broadway version, also deals with the choice of reading material better. Belle reads ALOUD from an Arthurian legend, which isn’t nearly as culturally inappropriate as it seems–the “Matter of Britain” was very popular in France. So it’s neither too difficult (since it’s read aloud) nor culturally weird (Shakespeare translations existed, but it’s still a weird choice).

P.S. Here I admit that I’m jumping straight into headcanon with no evidence in favor of this solution actually being in the heads of the production team, but the best solution I can find for the “age of the Prince” issue, which also neatly deals with the improbability of the restored Prince wanting to commission those stained glass windows, is that they were put in by a descendant of Belle and the Prince who is sort of a visual unreliable narrator, and who turned what was originally a story of hideous injustice into a morality tale because it fit genre expectations for that kind of art better. BTW I refuse to call him Prince Adam barring the Word of Glen Keane that that is his name. I can’t rule out that it might be, because Keane infused the transformation with a lot of personal religious fervor (DVD extras). . .but it just sounds WAY TOO MUCH like He-Man. Sorry.

P.P.S. My best solution to “So where was Maurice all that time?” is a simple, “The most sensible way to tell this story would be to have him ALREADY in the asylum. But an early modern asylum pushes the boundaries of a G rating way, way too far. Hence the unsatisfying waffle solution on film.

Howard Ashman had a lot to do with the excellence of both Mermaid and Beast. After his death, I don’t believe that any Disney animated film’s lyrics truly shone until Frozen. I love his internal rhymes: “What have they got? A lot of sand–we’ve got a hot crustacean band!” His lyrics have intricate delights and yet they always flow naturally, without any archness or awkwardness. I put him in the same category as Ira Gershwin and Irving Berlin.

Yes, Belle has more agency than some of the “princesses”–though Disney films are certainly getting better on that score. Also getting better on allowing the couple time to get to know each other before falling in love (shout-out to Tangled, here–not to mention Frozen‘s send-up of the “falling in love at first sight” trope). My problem with this movie as a feminist, though, is that Belle does fall in love with the Beast while he is still keeping her prisoner. He gives her a library, and I (as bookish as they come) want her to say, “That’s lovely, thanks, but I’d really prefer MY FREEDOM.”

Also, Belle is not animated in a very interesting way. This is a problem with most of the Disney “princesses,” who have to conform to certain expectations of shape and appearance. Marina Warner, in her From the Beast to the Blonde, points out that though the film theoretically focuses on Belle’s story, it’s the Beast who gets the animators’ and the audience’s attention. Finally, the movie is about maleness, its various forms (Belle’s father, Gaston, Beast), its need to be honored, matched and transformed. Not saying you can’t have a thoroughly feminist story about maleness…just saying that the Beast is much more intriguing a character than Belle.

I do think that they should have somehow made the restored prince more Beastly, too, to keep alive his vivid maleness. Maybe physical size, and gruffness, combined with a self-aware sense of humor as leavening….

Two things that have always bugged me about this movie:

1) The Beast has to learn how to judge people based on who they are inside rather than by their appearance … by falling in love with the most beautiful girl in town. I know, the story is Beauty and the Beast, so it’s kind of a given, but I have read re-tellings in which the “Beauty” was an ironic nickname given to a girl who isn’t a beauty. Or they could have left out that moral of the story, which isn’t so much in the original fairy tale. As I recall, there was no reason given for the curse. It wasn’t a punishment for being shallow. Disney added the moralizing about judging people on appearances, and no one in the creative process seems to have noted the irony.

2) Maybe the prince wasn’t wrong to turn away the scary old lady if her response to being snubbed was to put a child and all his servants under a curse. How did she know why he wouldn’t let her in? Maybe he sensed some serious stranger danger going on.

But I still love this one. The music is wonderful, though I wouldn’t mind an edition that includes some of the songs added for the Beast in the Broadway show. Robby Benson did fine in the one line in one song he got, so I felt like we were a little robbed by the Beast not getting a song. I liked that we actually saw a relationship based on interaction rather than one dance. By the end, you really feel like these two people love each other.

I saw Richard White on stage playing Lancelot in a production of Camelot, and I must say, that totally changed the way I view Gaston. The man behind the voice is more attractive than his animated counterpart, and he has that voice.

…if you want to know the answer to your timeline questions, servant questions and enchantress questions, the best thing to do is to read Robin McKinnley’s Beauty (1978). When the film came out, my first thought was, someone has read her book and not given her credit for the storyline! So many aspects of the story that Robin wrote, especially the relationship between the servants and Beauty are similar. There is much that is different, but I like to think that the two are connected.

Werechull – “The Morning Report” has far, far far far far far too many puns, and it’s markedly less well animated than the rest of the film, but it’s a bit less disruptive to the overall storyline than “Human Again,” which manages to break the mood and the plot, so I don’t feel the same need to warn off potential viewers.

Angiportus – That organ is in Belle’s Enchanted Christmas, the sequel that doesn’t really exist, no matter what Amazon.com and Disney might be trying to tell you.

Don S – At least one of the Disney DVD releases does not offer the option of seeing the film without “Human Again,” although I think the most recent release does.

Strongdreams – Sorry, I think this is one of those rare cases where even Tim Curry can’t save it.

Beastofman – For lunch, I honestly think most people are better off at one of the other Magic Kingdom restaurants – that place is loud. Granted, the other Magic Kingdom restaurants are also loud, but still. I haven’t tried the dinner, though. And I kinda have to admit that I was tempted by one of those light up goblets….

Mutantalbinocrocodile – Thanks so much for this detailed discussion. Oh, and although in retrospect it’s not clear, the six year old mentioned in the post isn’t me, but a kid that I later watched the film with who had a lot of questions.

Saavik – Yeah, the quality of the songs went down significantly after Ashman’s death – they’re not all horrible, but only a few of them are really memorable. I think Mulan, in particular, suffered from a lack of decent songs.

You and I are going to be disagreeing on Tangled, I can see.

The biggest problem with Belle in terms of animation is that over the years, she’s been animated by a number of people in different locations, and even in this film, she really didn’t have a single, supervising animator – which means that her face and body keep changing. You can really see this if you compare shots of her in the wolf scene versus shots of her just seconds afterwards back in the Beast’s castle – her hairstyle and face have changed completely, because she’s drawn by two different people. The other major characters had a single supervising animator who did a significant amount of the actual drawing work. That also means, as you say, that she’s less interesting – because no one wanted to take too much of a chance on a character that would be drawn by someone else in five more frames.

It gets much worse when you see her in other Disney features, as in House of Mouse, where her face looks almost distorted – but that’s in part because there really isn’t a good pattern for an artist to follow. She tends to be mostly recognizable either from the blue and white dress or the yellow ballgown.

Shawna Swendson – To be somewhat fair to the Beast, and to add to the reasons why I think the Enchantress is the real villain of the piece, none of the other villagers seem to be aware that he’s even there, so the Beast really doesn’t have a chance to fall in love with any of the other village women. I suppose he could have looked at some of them through his magic mirror, but I don’t know if he could have fallen in love with any of them that way. And all of the other women near him look like furniture, so I’m going to give him a pass on not falling in love with the feather duster maid.

I think Disney kept Belle beautiful partly as a nod to the two original French versions (where Beauty is beautiful), and partly because it’s in the Disney tradition. The images released so far for Moana seem to suggest that Moana is going to be considerably better looking than pretty much everyone else in her upcoming film, for example. (Not trying to offend the Rock here!)

I will say that Katzenberg noticed the irony – a scene in Shrek is meant as a commentary on it.

Most people call this Stockholm Syndrome, but the counter argument is it’s Lima Syndrome–where the captor ends up sympathetic to the captive, as the story is Beast going from a monster to a man (figuratively as well as literally). Belle’s influence on him and the castle is quite different from, say, Mother Gothel’s treatment of Rapunzel, or Frollo’s of Quasimodo, in those upcoming films–where the captive youths listen to, sympathize with, and even defends their captors for a long while before coming to the realization that their “parent” has been an abusive villain.

@14 – interesting perspective.

Anyway. I’ve enjoyed reading the post and comments. I loved this movie in part for having a bookish, bunette heroine :)

I really love the idea that the Enchantress is the villain of the piece and the Beast’s curse is more of an injustice/something to be overcome. It at least makes the idea that Belle is able to ‘reform’ him a bit more palatable if he really wasn’t that awful to start with.

@13 – uh oh, I suppose we’re going to disagree on Tangled too, heh.

Yesyesyes. This story is way problematic (“There is nothing so unnerving / as a servant who’s not serving”…gah), and as a lifelong lover of monsters and villains, I adore it. The stage version is among my favorite musicals.

Also, there’s an unintended tribute to the Luggage.

Tony Jay (Monsieur D’Arque) is oft noted for going on to voice Frollo.

The film’s TV Tropes pages contain a LOT of debate on ethics, character interpretations, and the logistics of the transformed servants, among other topics.

@Werechull: I heart the “Morning Report” song. Puns FTW…at least 13 of them, that I can remember offhand.

A nice touch in one of Angela Carter’s retellings of Beauty and the Beast (“The Courtship of Mr. Lyon”) — it ends by mentioning the human Beast has a broken nose which, together with his long hair, recalls his leonine form.

Thanks for the kind words, Mari. One further point that I think is in favor of the “sadistic Enchantress” (or, I’d argue more precisely, that the background artists as well as Glen Keane were on board with that one of the two conflicting interpretations on screen). The West Wing is markedly more physically distorted than any other part of the castle. It makes for some creepy visuals and maybe that’s all there is to it. . .but still, WHY are the royal apartments filled with gargoyles when no other part of the castle is? The rest of it looks frankly normal. Why is the doorpull into the royal chamber shaped exactly like the Beast’s head? It seems uncomfortably like an intentional pattern of psychological torture caused by the Enchantress.

Which then raises the other question, which I think might further flesh out the Beast–why does he insist on living in the most ghastly part of the castle, even after he’s trashed it in fits of fear and grief (those emotions fit his body language when ripping the portrait better than rage), even though presumably there are far more physically comfortable and less psychologically retraumatizing places for him to sleep all over the huge building? It starts to sound like a powerful visual metaphor for self-hatred.

Honestly, I think what a lot of my thoughts come down to is: despite being the first mainstream animated film to have a straightforwardly credited screenwriter, a huge amount of Beauty and the Beast is not really spelled out explicitly but left to the near-subliminal devices of visual storytelling. That would explain a lot about the way that it continues to powerfully and often inescapably appeal even in the face of all the “rational” reasons fans “ought” to stop loving it. Nostalgia on its own isn’t generally that strong. Reactions to visual art can be, I think.

This is the only adaptation of Beauty and the Beast that I know of that starts out by telling the audience or the reader that the beast has been cursed and needs the girl to help break the spell. It really is just as much about him as it is about her.

I honestly like the Beast’s reaction on finding Maurice – straightforward anger at a trespasser, rather than hospitality followed by “You picked a single flower so now you must die.” It’s not like the beast in that version knows that this guy has a daughter who he’ll be willing to swap for his life… It’s such a contrived setup, playing cat and mouse.

It really is huge that Belle makes the bargain herself. She’s not going along with her father because she is powerless, she takes it upon herself to make the offer to stay. And she does run away when the Beast goes too far and she is afraid for her life. And then when he has chased her through the woods – lucky he was able to fight off the wolves, but what if he’d caught her without that to stop him? – she could just leave him, but she has the compassion to save him. And then to stay, according to the original bargain.

And after watching her make these incredibly self-sacrificing choices, and becoming attached to her, the Beast is able to make his own sacrifice and let her go – no conditions whatsoever, and NOT telling her that he is doomed if she does not come back. That almost should have been enough to break the curse. There is a song from the musical called “If I Can’t Love Her”, and it is incredibly powerful – the beast realizing to himself that now that there is a chance, he is lost if he can’t find it within himself to be loving. https://youtu.be/GMXR_4_gX84

There’s also a song, “Home”, which is Belle telling the Beast in no uncertain terms that just because she has agreed to stay doesn’t mean he had the right to force her into that choice in the first place. https://youtu.be/_T-x8aRLrMY

The timeline is annoying to me. I always assumed that the references in “Be Our Guest” to having been isolated for ten years was just the liberties of a Broadway song – and my headcanon is that the introduction got the exact phrasing wrong. I don’t like the idea of it being a child prince who grows up as a beast. I think the spell put everyone in stasis. Otherwise half the staff, like Lumiere and his French maid, would have been children too at the time. And then there’s Chip – the child he turns back into at the end is not that old. Would Mrs. Potts really have been having children after turning into a teapot?

The comment about music going downhill from here on surprised me; most of my favourite Disney songs are from movies still to come. My absolute favourite is from Mulan. But then, I am not musical – I love songs but I can’t sing or tell scores apart or anything like that so maybe that influences it. I also realised, having gone to sleep with Be Our Guest earwormed last night, that they don’t get stuck in my head like that. I guess that makes later songs less memorable, but I’m not sure that’s a bad thing :p

I never loved Beauty and the Beast. I mean, I like it. I happily rewatch it and all, but that’s all. I’m not sure why. Belle’s animation contributed (and her snobbishness! I’m pretty sure I’m the only person who views her that way though, and she learns to get over that a bit as the movie progresses). But I guess it just didn’t hook me like it’s hooked so many others.

I love Tangled.

I wonder if the servants’ desire to serve is at least partially due to their transformation. It seems to be a recurring theme in fiction that animated versions of objects we think of as inanimate are eager to be useful. It kind of makes sense, in that not working is relaxing for humans, but dishes and knick-knacks that aren’t working usually just gather dust.

The other thing that this movie did, of course, was create a heroine who has to deal with the entire town thinking she is WEIRD because she LIKES TO READ. And then gave her the GREATEST LIBRARY IN THE UNIVERSE.

Anyone else identify with Belle just for that?!

@21 and everyone else on the servants, I guess I never generalized the couplet “Life is so unnerving/To a servant who’s not serving” to the entire staff; I took it as Lumière’s specific outlook (his huge number of backup dancers really only need to be incredibly bored for the scene to make character sense). It doesn’t bother me that specifically an upper-level servant (we never find out exactly what Lumière’s position is, but he seems to be in charge of rather a lot–maybe “butler” or “chief valet”) would feel that way about a career in household service. I suppose because I have actually met a few people whose career choice was some modern euphemism for “servant”. Anyway, it rings true to me that the top levels of the household might feel genuine pride in their jobs, and I’m not so addicted to grimdark that I really, really need to see things from the point of view of a miserable abused spit boy or teenaged chambermaid in a Disney movie.

At any rate, I’ve always taken the line mostly as Lumière coming as close as he can to infodumping the entire story of the curse onto Belle without literally breaking the implied house rule that “we don’t talk about that”. He consistently speaks and acts with enthusiasm bordering on desperation about breaking the curse, which the other adult servants never quite seem to want to talk about openly even among themselves, and he takes a much more substantive motive role than any of the others in maneuvering events in a direction that serves his interest without harming Belle’s (he suggests both the move out of the tower dungeon and the gift of the library). It seems fully in-character that he’d provide Belle with information she doesn’t necessarily need to know–that the castle has only been that way for ten years and not forever, that he has a normal human job title–without QUITE crossing the line into spilling all the beans.

@19: “The Mysteries of Teapot Reproduction” bordered on an Internet meme for a while. I agree that “stasis” is the simplest headcanon. Also agree that the reversal of the expected pronouns in the Broadway version (“If I Can’t Love Her”, not “If She Can’t Love Me”, at least in the first act) is a striking character choice which leans even further towards the “tormented Beast” interpretation, though I can’t help but wish Ashman had still been alive to write it. I don’t think Tim Rice really ever does his best work when he has to be 100% serious, without rage or black humor.

This was a very enjoyable movie, and the music and lyrics really made it shine. I liked the fact that in the struggle between bookworm and jock, the bookworm was triumphant.

The Disney folks did a nice job of incorporating the Beauty and the Beast attractions into the new fantasy land. I especially liked the fact that, on a blistering hot Florida day, we sat and ate next to a window where snow was gently falling.

I love this film, mostly for the library and bookish heroine I think. I’m also very fond of Robin McKinley’s two versions of the tale, Beauty and Rosedaughter, if anyone else would like to read them. Beauty has so many similarities to the film that I wondered if they’d used that as a source.

Both of them are very good, although different. I like them for different reasons. I read them about a year ago, and at the time I thought that perhaps Beauty had been influenced by the movie, until I checked the copyright date!

I guess the implications established in the prologue really bothered me because I woke up this morning realizing something: if the enchantress was powerful enough to curse the Beast and his entire castle, she could have created shelter for herself, just whipped up a little castle for the night. She also had the capability to appear lovely and unthreatening. She chose to appear in an ugly, frightening form, during a storm, in the middle of the night, asking for shelter she didn’t need. So, was this a sting operation? Was she deliberately trying to trap people into rejecting her, so she could curse them with righteous indignation? Is this the magical version of that awful “What Would You Do?” show (like Candid Camera, only judgey)? Her curse is way out of proportion for the offense, especially given that she was dealing with a child (maybe she’s related to Regina on Once Upon a Time).

But if the enchantress is meant to be the villain, it’s a rather unsatisfying conclusion because she’s forgotten after she makes the curse. She doesn’t reappear to be upset that her spell was broken. She doesn’t get defeated.

On the other hand, if we’re supposed to take it at face value that the Beast was being punished for looking at the surface and not at what was inside (even though the inside was pulling a sting on him, so maybe he was judging her on what was inside), then that arc doesn’t fit because that’s not what he seems to learn. He gets “tamed” in learning to love and be civilized enough that someone can love him, but it has nothing to do with appearances. He’s never re-tested on judging people by appearance so we can see where he’s learned and grown.

The story works a lot better if you just drop the prologue and accept the curse as something that just happened.

The reaction of the enchantress is perfectly reasonable. The message of the movie is that faerie people are jerks, so you should be carrying cold iron in all circumstances. Also, it is a specific kind of punishment that is found in quite a few fairy tales: the person who “wronged” the magician is condemned to live in the circumstances the magician was pretending to be in (and as @27 points out, it’s only pretend), until they can find someone who will treat them rightly. So either they are indeed jerks and the curse will be broken by the first person they meet, or they did what any person would have done and suffer for an eternity for it.

Hence, cold iron.

the beast doesn’t actually say he can’t read, he says he learnt ‘a little’.

the weirdest thing about this film is that the villagers apparently don’t know there’s a beast. a castle not far away – you’d think there’d be talk. also that they seem to think belle odd for reading, despite the fact that there’s a bookshop in the village – there must be other readers about, or how does the bookseller make a living? Belle though is unreasonable for expecting the villagers to listen to her chatter about books while they are working – can’t she see that they are busy?

Maybe most of the shop’s patrons are children, and Belle is unusual for being an adult who reads? That’s a good point, though.

They think Belle is odd for reading because she’s a woman.

I think two of the points in the article can be explained by follow:

“For instance, how did poor LeFou survive standing outside Belle’s cottage, covered in snow, for several days?”

I think he still had time to do his stuff in the village and got back to his spot as a snowman, it means everyday he left the place for a while and came back in his costume covered in snow.

“The Beast is largely fighting in self-defense, and it takes a moment before he’s even willing to do that. His first reaction to the arrival of the villagers is to say “it doesn’t matter now,””

I don’t think the Beast threw his servants into risks by refusing to fight back. He felt the meaningless of his life without Belle, and he had already lost all hope thinking that Belle would not come back. He had an enchanted mirror as the only connection to the outside world, and then he gave the mirror to Belle. Couldn’t only this detail show us how seriously he cared for her, forgave not only his chance to transform, but also all his connection to the remaining of the world. He said “it doesn’t matter now” without knowledge of his servants were willing to fight for him. His servants had their choices, though. The song “Human Again” shows us how exciting they were to the chance of their transformation, thus it’s reasonably to see why they were all sad and hopeless after Belle left the castle. When Gaston and the villagers wilted the castle, they had a choice to remain silence as normal objects or fighting back, for all the villagers want was the Beast. What I love about this film, is how they portrayed the loyalty of the servants to their master. Even when the Beast failed his, and all their chances to become “Human again” by releasing Belle, they still tried everything to help out their master until the very last minute. And that was not forceful for them to do so. No villagers would hit ordinary furniture, if the servants pretended to be ones. After all, villagers came to castle for the Beast, not the enchanted objects.

The AV Club does a look back.

http://www.avclub.com/article/25-years-later-beauty-and-beast-remains-disneys-be-244691

My absolute favourite Ashman rhyme from this film comes from “Gaston”:

As a specimen / Yes, I’m in- / -timidating!

Spec-im-en, yes-i’m-in! The man was a lyrical genius…

Brenda A. @19 – I absolutely agree with you regarding “If I Can’t Love Her.” It ranks within my top 3 Act I finale songs from all the Broadway shows I’ve ever seen, and is probably the top list for those that are solos. It’s an incredibly powerful song, and, while I agree with what mutantalbinocrocodile pointed out @23, about it pointing to the Beast’s self-realization that something about him has to change before anything else matters, I think the reprise in the second act is even more heartbreaking. He’s freed Belle (to the extent that she was still actually a prisoner) and given her, as Annechua pointed out @32, his only link to the outside world. He clearly loves her, but is painfully aware that this is only half of the equation.

Count me as one who is disappointed that these songs aren’t going to be in the live-action version this Spring.

VERY late to the party here…

”Beauty and the Beast” is one of my top-10 favourite films, for a whole bunch of reasons. I literally just re-watched it about two hours ago, and something struck me that I hadn’t noticed before (and which perhaps was more apparent to me because of recent events in the U.S.) – Belle is basically SEXUALLY HARASSED through the entire film. But she FIGHTS BACK. And she never stops fighting. I appreciate that message now and think one of the reasons I loved the film so much when it came out was because of that.

I know the film may be kind of dated but I think it actually presents a decent portrait of female agency. Belle CHOOSES to take her father’s place in the Beast’s castle. She refuses to eat dinner with the Beast. She explores the West Wing despite the Beast’s “prohibition.” She runs away when he gets too abusive and seems to be doing a pretty good job of fighting the wolf pack until the Beast shows up. Then she basically saves the Beast’s life by getting him back to the castle and dressing his wounds – not to mention that she yells back at him when he snaps at her! Belle also always shoots Gaston down pretty eloquently (and, BTW, I cannot BELIEVE that I spend so many years missing the homoerotic sub-text in this movie, which DEFINITELY problematizes things!).

I know that my reading of the film is coloured by my personal life; I first saw it when I was (unfortunately) dating someone who was very much like Gaston. Many years later, I met my current partner who, I am NOT kidding, looks VERY much like the Beast. He is a big guy who is kind of “fuzzy” and has bright blue eyes. And, also not kidding, I recognize some of his facial expressions in the film. While I am not as pretty as Belle, I DO have dark hair and hazel eyes and around the time the film came out, I tended to style my hair in a style similar to Belle’s.

Again, very late to the party, but just chiming in on one of my favourite movies!

Correct me if I’m wrong, but aren’t there versions of the story where the father promises the Beast his daughter?

Doesn’t stop Belle from fighting, but it does put a different spin on her father, though I suppose it could be ameliorated somewhat with the right dialogue.

But yeah, there’s guys like Gaston out there, and some of them to get their Beauty. More’s the pity. Excuse me I need to tear up something.

The versions I know the father mentions his daughter to explain why he took the rose and the beast says in essence come back and get killed or send your daughter. The father tells his story to his daughters and Beauty insists on keeping the bargain while her father argues for going back himself his reasoning being he’s old and he’s a failure and so no loss. Beauty’s that he is going to certain death while the Beast hasn’t threatened her. She wins.

38, yes, that’s one of the versions that more or less takes the onus from the father. There’s others, that are a little darker.

@LordVorless: I’m well aware and that is one of the reasons why I love the film so much, I think. IMHO, a lot of women have fathers who dictate what they should do in one way or another. (Please be aware that I am white and cisgender; also, my background and sphere of reference is the U.S., so this may not apply to all places, cultures, and people.) While I personally think my dad was better than a lot of other fathers, I DO remember times when he dictated things to me and to my mom and sisters, many of which didn’t seem to make much sense. In Disney’s version, Belle voluntarily goes to save her father and persists even when he begs her not to do so. He isn’t ordering her around at all. Nor does she let the Beast ever order her around.

And yes, there are far too many Gastons out there. Happily, the Disney film kind of warned me away from the Gaston in my life at the time (I was VERY young and it wasn’t a serious relationship at all) and later, when I was older and could have gotten into a relationship with another Gaston, who was pursuing me kind of like Gaston pursued Belle in the film. And (NOT KIDDING), there was actually kind of a show-down when my current partner (my “Beast”) took on “Gaston” while “Gaston” was sort of trying to take advantage of me when I wasn’t in a fit state to grant consent. Unlike in the film, no one died, but “Gaston” backed the heck off and I landed up with the “Beast,” in a relationship that has lasted well over a decade. I do hope that the Disney film, despite the obvious “Stockholm Syndrome” theme, has encouraged viewers – particularly female viewers – to look more carefully at the men in their lives and look beyond a handsome face. (And have I mentioned that I think the Beast is WAY more handsome than Gaston?)

I also forgot to mention in my last post that I have always been a bookworm (I currently have a Ph.D. in English and teach literature at the college level) so I completely related to Belle’s love of books. That library is my DREAM! (Alas, I live in a small apartment, so that will probably remain a dream. I am not sure I can physically cram any more books and bookshelves into our apartment.) When I first watche “Beauty and the Beast” it felt like Disney had finally made a movie JUST FOR ME.

Wow, I’m having my feels all over this website, aren’t I? ;) It’s a pleasure to talk about this film and talk to others about it. I am *vaguely* thinking of writing something about Disney films and Disney princesses for an upcoming article, so I’ve also got Disney on the brain recently. :)

I believe there’s a cure for that affliction. Watch the Black Hole and your brain will shut off and reboot. If that doesn’t work, try one with Don Knotts.

But yes, I imagine the library and Belle’s love for books appealed to many many people. (It is my personal vice as well.) And no doubt a lot of compassion as far as being surrounded by critics of that love go.

Speaking of books though, have you read the Mercedes Lackey 500 Kingdoms versions of fairy tales?

@LordVorless – Yes, I know about and have read many of the “500 Kingdoms” books by Lackey! I am also a big fan of the re-told faerytale series that began with “Snow White, Blood Red,” edited by Ellen Datlow. T. Kingfisher (who I think is a Tor author) also has a lot of books and stories that are, at least to me, utterly *charming* re-tellings of classic faery tales. (Seriously, how is Kingfisher NOT better known?!?) I especially love her “Snow Queen” re-telling: “The Raven and the Reindeer.”

Have you read Caitlin R. Keirnan? (Recently she’s released some stuff through Tor.) But one of her early short story collexions, “Tales of Pain and Wonder,” was basically made up of VERY dark re-tellings of faery tales, from “Glass Coffin” as an even bleaker version of “Sleeping Beauty” to “Tears Seven Times Salt” as an inverted “Little Mermaid.”

(Note: “Tales of Pain and Wonder is out of print currently; the editions that show up first on Amazon and eBay tend to be VERY expensive. However, a little hunting online WILL turn up much cheaper copies.)

In my literature classes, I often ask my students, as an assignment, to “re-write” a faery tale with which they grew up (I usually assign this after we’ve read some of Kiernan’s stories, or some of Anne Sexton’s poems like “Cinderella”). Always, some of the students run with it and do an incredible job, but usually just as many can’t seem to even *conceive* of re-writing these stories with which they grew up, and which they see as “unchangeable” narratives.

So, this brings me back to “Beauty and the Beast.” On a very basic level, I read the original tale (well, as much as there IS an original tale) as a narrative of a woman being abused by her father and husband and, ultimately, being told that if she puts up with the abuse she’ll win a “prince” and entrance into the aristocracy. Yet the Disney film (and I’m aware that ALL MY FEELS may be getting in the way of me being able to objectively analyze the film), to me, seems to subvert that message. Belle “puts up” with absolutely NOTHING. She actively drives the plot; unlike earlier Disney princesses, things do not “happen to” her – she actively makes choices that shape her life. And let’s not forget that at the very end SHE saves the Beast’s life after riding to HIS rescue!

PS: I’m well aware that vaguely *thinking* about writing an article about Disney films may be the first step to tumbling down a dangerous rabbit hole (pun intended). My sister, who is also a college professor but who works in Art Education, is doing a project on princesses in general and Disney Princesses specifically for her sabbatical. And she IS having some trouble.

PPS: LET US NEVER AGAIN SPEAK OF “THE BLACK HOLE.” In my world, that film does not exist and NEVER SHOULD EXIST IN ANY POSSIBLE REALITY.

42, yes, I remember the Snow White Blood Red book as well, haven’t read Caitlin R. Keirnan but I’ll try to keep an eye out for her now. She’ll go on the list. (one of my worst hauntings is the number of times I’ve seen a quality book I could have picked up and didn’t because I hadn’t yet heard of them.)

Speaking of rewriting stories in classes though, that’s actually something that happens in the Merchants’ War by Frederik Pohl. I can’t recall what story he rewrote, but I think he set it in Nazi Germany for some reason. A lot of people have that problem though, they don’t realize that a story is often a set of pieces that can be re-oriented to tell a whole different version. Maybe you should play Rashomon for them? Or some shorter version, it has been re-adapted.

But going back to Beauty and the Beast, you’re certainly making good points about the Disney film making more of an effort to give her a role, unlike some others in their animated canon, Belle is a character who does act on her own accord, which is also true of the Little Mermaid and Aladdin (to name the most contemporary films). Ariel, Belle, and Jasmine, were not entirely set-pieces, but could be said to do things. Still, I do find myself troubled a bit by how all three of them ended up with just the right man. (And even Miss Bianca!) Because that’s the way things are supposed to be.

Oh well, at least the Tangled tv series (the movie is another instance of the Princess finding the man, too bad it took the death of Flynn Rider), is giving Rapunzel something to do with her life that doesn’t always entirely revolve around the man.

PS, I’m really worried about Frozen 2 when it comes to that.

PPS, brain bleach so powerful that it denies its own existence.

@LordVorless: PLease DO read some Kiernan. Her work is basically beyond incredible, and a lot of it (aside from “Tales of Pain and Wonder”) is currently available as Kindle books very affordably. Aside from her re-told faery tales, she’s written a lot of what we might call “hard Sci-Fi” (some of her best is collected in “A is for Alien” and I ESPECIALLY recommend “Faces in Revolving Souls). She has a Master’s degree in prehistoric invertebrate paleontology so, unlike some other SF writers, she really DOES know her sh!te.

I cringe to admit that I’m not a huge Pohl fan. I’m actually not entirely sure why; I can recognize his skill on a technical level but somehow his writing has never really drawn me in. I am not familiar with “The Merchant’s War” but I am betting that my partner (my “Beast”) is – he’s a big fan of alternate history narratives and really likes Harry Turtledove. I will ask him what he thinks of it. But I think that setting your narrative in Nazi Germany can be problematic, at best. I have had a whole bunch of students who got VERY upset about Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy” for just that reason.

I’m totally with you about how problematic it is that many female Disney characters “land up with just the right man.” Since I’ve already had all my feels all over these comments, I might just as well keep going and disclose that I’m a Queer woman. I am with my current male partner not necessarily because he identifies as male, but because we fit well together. If I’d ever met a woman about whom I felt as strongly, I’d be with her. I am NOT nuts about the continuing heteronormative bias in Disney movies – and I certainly HOPE that “Frozen 2” won’t pair Elsa up a man. I seriously hope that the positive fan response suggesting Elsa may be Queer, Aromantic, or Asexual will convince the powers that be at Disney to NOT force her into a heteronormative story!

In regards to “The Little Mermaid,” which was the first of the “Disney Renaissance” films that came out before “Beauty and the Beast” – yes, I agree that Ariel was stronger and had more agency than earlier Disney Princesses. However, I don’t think that she had the same kind of agency that Belle (and subsequent Disney Princesses) do. Ariel basically comes across as an impulsive teenager (which, IIRC, Mari Ness pointed out in her excellent post on that film). Ariel falls in “love” with a conventionally handsome prince based upon her journey to the world above and a statue of him she found. And then she is deprived of her voice (as so many women are) and has to “seduce” Prince Eric somehow. Ariel’s basic motivation is “I WANT TO LAND PRINCE ERIC PLZ.” (Pun kind of intended.). And there is also the VERY problematic nature of Ursula’s character; again, Mari Ness addressed that better than I can. But there is also another layer of complexity there – it has been pretty well documented that Ursula was based on Divine, who was a famous (and gorgeous) drag queen.

(The Queer subtext in Disney films probably deserves its own post.)

Meanwhile, Belle does NOT initially want to get married; she wants “adventure in the great wide somewhere.” And she gets that – plus *the library of my dreams.* I also think it’s notable that “Beauty and the Beast” was, IIRC, the FIRST major Disney movie that didn’t show women fighting against other women. There was no “evil queen” or “evil stepmother” or “evil sea-witch” or “evil witch who wasn’t invited to the party.” Instead there is a smart, competent woman who doesn’t meet some conventional beauty standards in the U.S. who also *literally* saves two men (her father, the Beast) and stands up to her harraser (Gaston).

Also, if you get a chance, DO READ “The Raven and the Reindeer;” I don’t want to spoil the story, but I’ll just say that it completely subverts some of the concerns you’ve mentioned about faerytales.

PS: I am probably dating myself here, but I saw “The Black Hole” in a DRIVE-IN. My dad, who is a computer design engineer (I *think* at that time he worked for the now-gone company Adar, which was bought out by Scientific Atlantic, which in turn was bought out by Teradyne – IIRC. He currently works for Analog Devices but is coming up on retirement soon), was SO MAD about the science – basically the lack thereof – in the film.

I had a similar reaction to “Event Horizon.” I’ve got a Master’s in physics and for a while wanted to be Stephen Hawking, but finally realized that I basically wanted – and would be better at – teaching and (maybe) writing science fiction than actually being a scientist. While the science of “Event Horizon” is *beyond* terrible, I realized I was more interested with the (non-scientific) ideas of holes in reality, and the possibility of slipping into alterate (Freudian) dimensions, and how a creator might be intimately tied to their creation. (I had a wee bit of experience with that – I was part of the TERRIERS satellite team at Boston University – google it – and literallly *touched things that are now in space.* But the satellite has now become space junk because there was a problem with the torque coils and the solar panels. I would like to add that I had NOTHING to do with that part of the satellite. In all fairness, I also have to admit that I was an undergrad who was basically an “intern” on the project; I just basically did whatever I could to help the project leaders who knew a LOT more than I did and even do now. For example, my biggest assignment on the project was to build a LOT of cables to use for tests in the clean room. But hey, I learned how to braid wires and how to solder (and that a soldering iron REALLY hurts if you touch it by accident).

But even though that I didn’t CREATE the TERRIERS satellite, I DO understand how someone (cycling back to Sam Neill here), could have so much of their identity wrapped up in their work that they could literally go insane over it

Okay, I am pretty much rambling at this point, but I must say again that it is a pleasure talking with you! :)

44, in the Pohl book, the alternative work was very obliquely mentioned, and I’m not even sure it was Nazi Germany, it might have been something else, and I’m totally foggy on what it was the main character was adapting.

In the Little Mermaid, yeah, she is doing it all for a man, who she doesn’t know, but apparently thinks is dreamy or whatever. Not that Erik is a bad guy, but the credit I can give her is that she wasn’t sleeping in a glass sarcophagus after eating an Apple or stabbed by a needle, she was doing something, and she had her own life. Sure, it upset Daddy, but well, eventually he learned.

Beauty and the Beast…that does bring up a good point about female-female conflict I hadn’t considered directly, though I had always hated how like every stepmother and so forth was supposed to be evil and jealous, and the poor man was a victim seduced into it. I suppose Pinocchio might not have such a conflict? Maybe the Aristocats.

I do hope you’re right about Frozen 2.

PS, Soldering irons hurt if you touch them on purpose too, even if your purpose is dumb (Hey, is this getting hot yet…ouch!)

The thing about Ariel is that at least she is established, even before falling in love with Eric, as somebody who is interested and curious about human culture – but then that whole part of her got subsumed with the romance subplot. Perhaps in a remake she can be a budding human anthropologist ;)